You might be asking: What is Free Kriegsspiel?

And if you already know what it is, you might then ask:

What does it have to do with Dungeons & Dragons?

And if you know that, you might still wonder:

Why does it matter today?

Well, let’s dig into all of that.

The Birth of Wargaming

In the early 1800s, the Prussian military developed Kriegsspiel, a revolutionary tabletop wargame used to train officers. Designed with strict rules and procedures, it aimed to simulate battlefield tactics with dice used to calculate losses. Every action had a reference; cannon ranges, troop movement, terrain effects, all locked into rules and charts.

But war, as any commander knows, doesn’t play by rules.

What happens when a rainstorm washes out the only road to the front? Or a sudden fog descends on the battlefield? What if your gunpowder’s damp and your cannons fire high and blind into the mist? You won’t find the answer in a tidy table on page 214.

The real world is messy. Edge cases are not rare, they’re the norm.

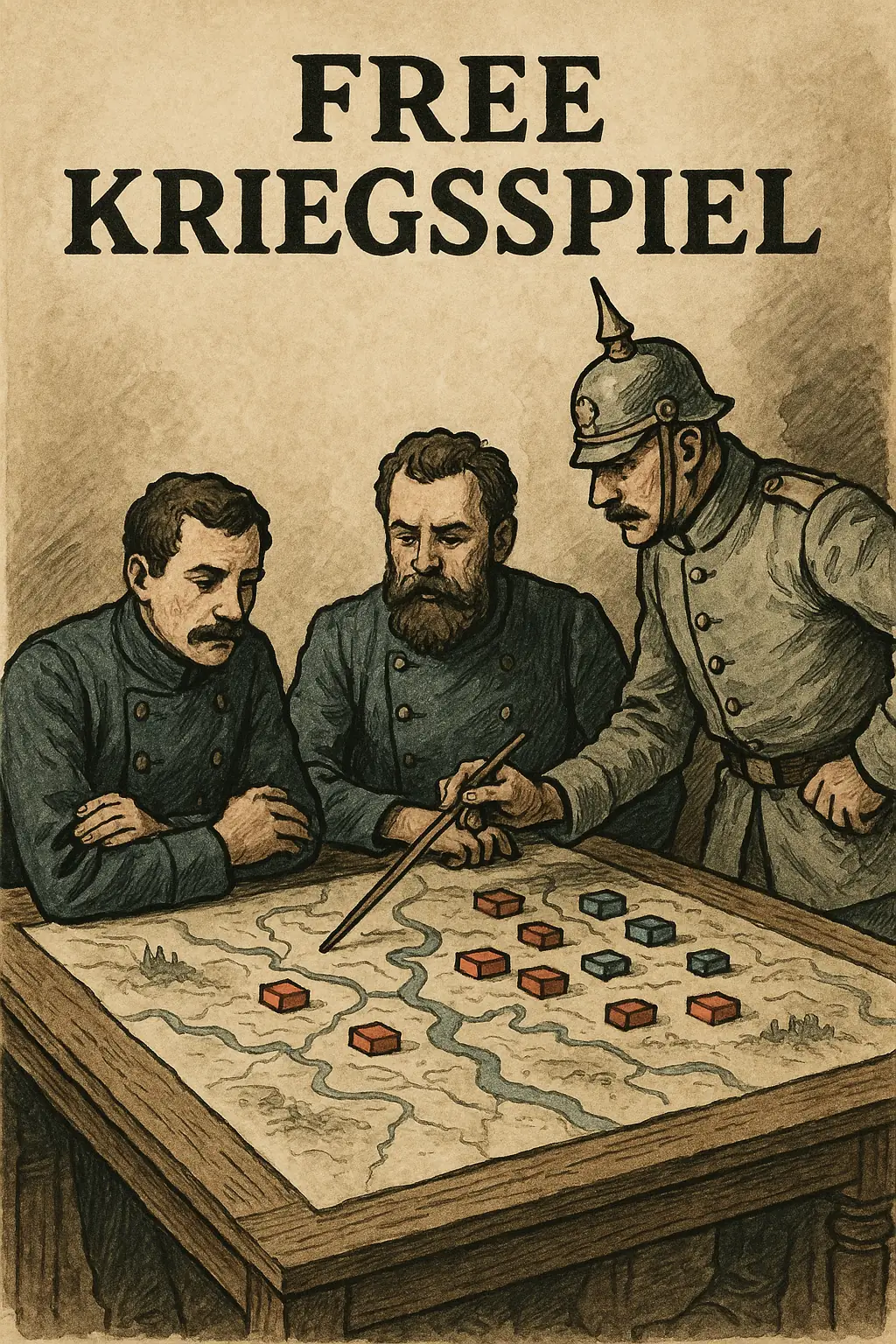

Enter Free Kriegsspiel

To better reflect this chaotic reality, Free Kriegsspiel emerged. Around the mid-19th century, rather than rely on rigid rules, this version of the game empowered a Referee (usually a seasoned military officer) to interpret situations and make rulings on the fly. There were still basic mechanics, but the game’s soul was in the judgment of the Referee.

This Referee didn’t just adjudicate. They became the world. Their knowledge, instinct, and creativity shaped every scenario. It wasn’t about simulating war with rules, it was about understanding it through dynamic, human judgment.

Strategos: Free Kriegsspiel Crosses the Atlantic

In 1880, an American military officer named Charles A. L. Totten published Strategos, a detailed adaptation of Free Kriegsspiel for the U.S. Army. It blended rules and rulings, and was explicitly designed for teaching tactics and decision-making. It included structured procedures, but also clear instructions on how a Referee should manage uncertainty and improvise within the game.

Strategos wasn’t just a game, it was a tool for shaping officers into critical thinkers.

The Secret Thread to Dungeons & Dragons

Fast-forward to the 1960s. Historical wargaming, especially Napoleonic and Civil War battles, was a major tabletop hobby in America. One particularly active group in the Twin Cities (Minnesota) included Dave Wesely and Dave Arneson.

Wesely stumbled upon a copy of Strategos in the library and noticed that other local wargamers had checked it out before. It was a kind of secret scripture among serious players.

Inspired by Strategos, Wesely created a game called Braunstein, set in a fictional Napoleonic-era town. But unlike traditional wargames, players weren’t just generals. They were also mayors, spies, diplomats, and nobles. The Referee (Wesely) had to adjudicate not just battles, but backroom deals, lies, schemes, and negotiations. Players even wrote letters between sessions proposing treaties or sending secret orders.

One of the most active and creative players in Braunstein was Dave Arneson. He played cunningly, used misinformation, spies, and forged letters to outmaneuver others. He broke the game in the best way possible and everyone loved it.

Blackmoor and the Fantasy Leap

Inspired by Braunstein, Arneson created a new setting: Blackmoor. The very first fantasy TTRPG campaign. The idea was simple but revolutionary, apply the Braunstein/Free Kriegsspiel philosophy to a fantasy world. Players weren’t generals or mayors anymore. They were adventurers: wizards, warriors, thieves, and clerics exploring dungeons, interacting with NPCs, and changing the world.

There weren’t real "rules" the way we think of them today. There were few stats on paper, d6 rolls, and rulings made by the Referee, Arneson himself. If you tried something risky, he might say, “Roll a d6, you succeed on a 5 or 6,” or change the odds depending on the situation. Arneson was the world. The judge. The law.

Gygax Enters the Dungeon

Arneson eventually showed Blackmoor to Gary Gygax, a fellow wargamer who had co-created Chainmail, a miniature wargame with some fantasy elements. Gygax saw the spark in what Arneson was doing, this wasn’t just another wargame. It was something new.

Together, Arneson and Gygax began codifying the rules that existed only in Arneson’s notes and head. What should happen when a player tries something bold? When should a roll be called for? What are the odds?

The result was the original 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons, often called OD&D. It came in three little brown books. And it was full of gaps, intentionally.

Because the Referee (or Dungeon Master, as it was soon called) was expected to make rulings, not just follow rules.

From Rulings to Rules

As D&D’s popularity exploded, so did the number of questions:

- What if a character wants to sneak past a guard?

- What if they want to seduce a princess?

- What happens if a spell goes wrong?

TSR, the company behind D&D, was flooded with letters. Players wanted clarity.

So D&D began evolving into a more rules-heavy game. With each new edition, Holmes Basic, AD&D, and beyond, the rules grew more detailed, the edge cases more defined.

Holmes Basic was arguably the last version that truly embraced the Free Kriegsspiel spirit. After that, it was mostly about rules first, rulings second.

Why It Matters Today

Understanding the origins of D&D in Free Kriegsspiel changes how we see the game. It reminds us that D&D wasn’t born as a system of fixed mechanics. It was born from creativity, improvisation, and human judgment.

Original Dungeons & Dragons wasn’t a fully self-contained manual in the way modern rulebooks are. It referenced Chainmail for combat resolution, Avalon Hill game, Outdoor Survival and often assumed the reader had access to other wargaming systems. For example, OD&D states that:

“The referee must decide what constitutes a ‘reasonable’ action on the part of the players, and what is ‘reasonable’ will vary from referee to referee and from situation to situation.”

This wasn’t an oversight, it was intentional.

I believe Gygax and Arneson expected, perhaps even assumed, that referees already understood what it meant to run a game: to make calls on the fly, to improvise, to use other systems, and to prioritize rulings over written rules. They were drawing from their experience with Braunstein and its Free Kriegsspiel DNA, the foundations that gave birth to Blackmoor, and ultimately, to D&D itself.

To those unfamiliar with this lineage, OD&D can seem incomplete or vague. But that openness isn’t a flaw; it’s a feature. The game trusts the referee. It hands them the tools and says, “Now build your world.”

This is the heart of the philosophy: Rulings, not Rules..

In a time where modern RPGs often come with 300-page rulebooks and rules for everything, it’s refreshing to remember this: the most powerful engine in any game isn’t the system, it’s the people at the table.

The Era of D&D Evolution

Over the decades, Dungeons & Dragons has gone through distinct evolutionary phases, each marked by a different relationship to rules, rulings, and the role of the Referee (or Dungeon Master). Here's a way to break it down:

1. Rulings Not Rules (1974–1979)

Rooted in Free Kriegsspiel

This is the original era, beginning with OD&D, the Little Brown Books. These rules were more like guidelines. The assumption was that the Referee (inspired by Free Kriegsspiel tradition) would make ad hoc rulings based on the situation, logic, fairness, and fun. Much of the game lived in the Referee’s head and on scraps of paper. If something wasn’t covered by the rules (and most things weren’t), the Referee made a call.

This style survives in the Holmes Basic Set (1977), which still leaned heavily on open-ended rulings and assumed the Referee was a creative adjudicator, not a rule-bound technician. Holmes was the last of this era.

2. Rulings Over Rules (1981–1991)

The Birth of Formalization

The release of the Moldvay Basic and Cook Expert sets (1981), followed by Mentzer’s BECMI series (1983–1985), marked a shift toward clarity and structure. The rules became more accessible and better organized, yet still left space for rulings when needed.

Around the same time, Gary Gygax launched Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (1e) as a response to the perceived chaos of OD&D. The original game required referees to make frequent judgment calls, leading to wildly different tables. AD&D aimed to codify and unify the OD&D rules and supplements, especially for tournament and convention play. While part of this move was about standardization, it’s hard to ignore the business motives; rights, licensing, and control over the brand also played a role.

Referees still held authority, but the push for consistency meant more procedures, charts, and systems. This era culminated in the Rules Cyclopedia (1991), a single-volume consolidation of BECMI that preserved room for rulings, but placed them atop an increasingly dense rule structure.

This decade reflects a fundamental tension in RPG design: players and referees cherished the open-ended spirit of OD&D, but many also wanted clearer guidance. TSR tried to serve both, and the result was both an evolution and a departure.

3. Rules Adjudication Era (2000–Present)

The Age of Codification

With D&D 3rd Edition (2000) and especially 3.5 (2003), we enter a new phase: the game becomes a complete, internally consistent rules engine. Everything is spelled out. Every action, every modifier, every edge case. The DM’s role becomes one of a rules adjudicator rather than an improvisational storyteller. This era is marked by design philosophies like "system mastery" and "balance," and by the explosion of feats, skills, and keywords.

D&D 4th Edition (2008) pushed this even further, turning the game into something resembling a tactical miniatures board game.

5th Edition (2014/2024) attempted to return some narrative flexibility, but it still relies heavily on rule adjudication. Even when it nods to “rulings,” it does so within a system that assumes a shared rules foundation between players and DM.

This is the current mainstream, where clarity and consistency are king, and the Referee is more a judge of rules than a creator of outcomes.

Each era of D&D reflects a different attitude toward imagination, authority, and uncertainty. From Free Kriegsspiel's trust in the Referee's judgment, to modern D&D's structured adjudication, the pendulum has swung back and forth between freedom and formalism.

Understanding this evolution isn’t just a history lesson, it’s a reminder that you can choose what kind of game you want to play.

Is Anyone Still Playing OD&D?

(And What About Free Kriegsspiel and Braunstein?)

The answer is - thankfully - yes, and the community is growing.

OD&D, along with versions of David Wesley’s original Braunstein (like Barons of Braunstein), are available on DriveThruRPG. But beyond simple availability, the last two decades have seen a quiet but steady resurgence of interest in the roots of the hobby.

In the early 2000s, the Old School Renaissance (OSR) emerged, a response, and in many ways a rebellion, against the rising complexity of 3rd Edition and especially 3.5. Many players wanted to return to the games they grew up with: AD&D, B/X, and even OD&D. But those editions were out of print, their rules scattered across aging manuals and hard-to-find zines.

The OSR brought them back to life; preserving, hacking, and reimagining them. What began as nostalgia became a movement.

Enter the First Retro-Clones

The early wave of the OSR brought us OSRIC (for AD&D) and Labyrinth Lord (for B/X), soon followed by Old-School Essentials (OSE), which gave Moldvay’s B/X ruleset a beautifully clean, modern layout. These games reintroduced a generation to classic editions and sparked a flood of new titles, adventures, and zines. Most clung closely to the bones of AD&D or B/X, but somewhere beneath the surface, interest in the rawer, wilder roots of OD&D had begun to stir.

The FKR and the Return to the Source

By the late 2010s and early 2020s, a new current emerged within the OSR: the Free Kriegsspiel Revival (FKR). This movement looked beyond Gygax, back to David Wesley’s Braunstein and the freeform wargaming traditions that shaped Arneson’s imagination and led directly to OD&D.

FKR is more than minimalist, it’s a philosophy of play. It places trust in the Referee. It values shared fiction over mechanical precision. It isn’t concerned with balance, builds, or tactical optimization. It’s about ruling the world as it’s imagined, not as it’s quantified.

Early OD&D-inspired clones like Swords & Wizardry and Delving Deeper laid the groundwork, but today, we’re seeing renewed and growing interest in the earliest forms of the game, not just as nostalgia, but as a living, breathing approach to roleplaying.

Games inspired by an earlier era.

This isn’t a complete list, but these are the games I know (own and/or have played) and they offer a great starting point for anyone interested in exploring the rich, imaginative world of early D&D-style fantasy roleplaying. Each captures a different spirit of the original games, from faithful retro-clones to freeform interpretations rooted in the hobby’s earliest days.

OD&D Retro-Clones “Rulings Not Rules”

Loose, referee-driven systems. Inspired by the 1974 white box and early FKR principles.

- Swords & Wizardry - Matt Finch. The most well-known OD&D clone. Several editions exist (Core & Complete). Emphasizes referee rulings.

- Delving Deeper - Simon Bull & Cameron Dubeers. Very close emulation of 1974 OD&D plus its supplements. Textual fidelity to the original.

- White Box: Fantastic Medieval Adventure Game - Charlie Mason. A lightweight OD&D clone. Open, modular, and beginner-friendly.

- Blueholme - Michael Thomas (Dreamscape Design). Based on the Holmes Basic D&D edition (OD&D + structured editing). Two versions: Prentice Rules and Journeymanne Rules.

- Lion & Dragon - Daniel J. McCoy (RPGPundit). A "medieval authentic" OSR system based on OD&D, with a gritty, historical tone. Strong focus on low magic and realism.

- Iron Falcon - Chris Gonnerman. Companion to Basic Fantasy RPG, but based on OD&D rather than B/X. Clean and retro.

BX Retro-Clones “Rulings Over Rules”

BX-style structure, modularity, and clarity. Based on Moldvay/Cook/Marsh B/X, Mentzer BECMI and AD&D (1e).

- OSRIC (Old School Reference and Index Compilation) - Stuart Marshall & Matt Finch. Emulates AD&D 1e rules to support new content creation. One of the first retro-clones.

- Old-School Essentials (OSE) - Gavin Norman (Necrotic Gnome). Meticulous B/X clone, clean layout, modular books. Gold standard in usability.

- Labyrinth Lord - Daniel Proctor (Goblinoid Games). A well-established B/X clone. Compatible with B/X and AD&D elements.

- Basic Fantasy RPG - Chris Gonnerman. A beginner-friendly B/X clone using modern mechanics like ascending AC. Completely free and open-source.

- Lamentations of the Flame Princess (LotFP) - James Edward Raggi IV. A weird horror take on B/X with evocative spells and deadly consequences. More adult and philosophical in tone.

- The Black Hack - David Black Though rules-lite and modern, it draws heavily from B/X sensibilities. A fast-play, rulings-friendly system.

- Shadowdark RPG - Kelsey Dionne (Arcane Library) A modern evolution rooted in B/X structure with heavy emphasis on rulings, dungeon exploration, and real-time torch mechanics.

My Personal Favorites

While I haven’t played every retro-clone out there (who has?), I’ve explored quite a few and developed some firm favorites. These are the games that, for me, capture the essence of the eras they seek to emulate and sometimes even transcend them.

OD&D Favorites – “Rulings Not Rules”

Swords & Wizardry is my go-to. It brings the best of OD&D together into a clean, cohesive system. The combat phases allow for classic spell interruption, the single saving throw is elegant and fast, and the class design is as simple as it gets. For me, S&W embodies the spirit of OD&D, lightweight, referee-driven, and flexible.

I also want to highlight Lion & Dragon. While the mechanics are rooted in OD&D, it’s the setting and tone that shine. It captures a truly early medieval, low-magic, gritty fantasy like few others. That said, the real gem (from the same author) is Dark Albion. If Lion & Dragon is a dagger, Dark Albion is a longsword. It expands everything into a full-blown medieval sandbox steeped in historical realism and political intrigue.

My favorite combo? Use Swords & Wizardry as the rules engine, pair it with Dark Albion as the setting, and you’ve got yourself a masterclass in old-school, Free Kriegsspiel-inspired low fantasy.

BX Favorites – “Rulings Over Rules”

Like many, my D&D journey began in 1982 with Moldvay Basic, so Old-School Essentials (OSE) naturally lives on my shelf. It’s beautifully organized, crystal clear, and adds the modern bonus of ascending AC. It scratches that nostalgia itch perfectly.

But if I am feeling for something different, the two B/X-adjacent systems I actually reach for most are:

Shadowdark, for its brilliant distillation of BX principles into a fast-paced, modernized dungeon crawler. It nails the spirit of exploration, danger, and real-time tension with streamlined rules and evocative flavor.

The Black Hack, for giving the OSR a breath of fresh air. Its player-facing rolls, minimalist mechanics, and flexible gameplay make it a perfect rules-light option that still feels gritty and old-school.

The Truth Is…

We’re incredibly lucky to be living in a golden age of rediscovery. Dozens of creators are reimagining, refining, and honoring the legacy of early roleplaying. Whether you're chasing pure nostalgia, medieval grit, or a modern rework of classic mechanics, there’s something for everyone.

But this isn’t just luck, it’s a testament to the enduring power of a philosophy that began with Free Kriegsspiel, Wesley’s Braunstein, and a couple of curious wargamers named Arneson and Gygax.

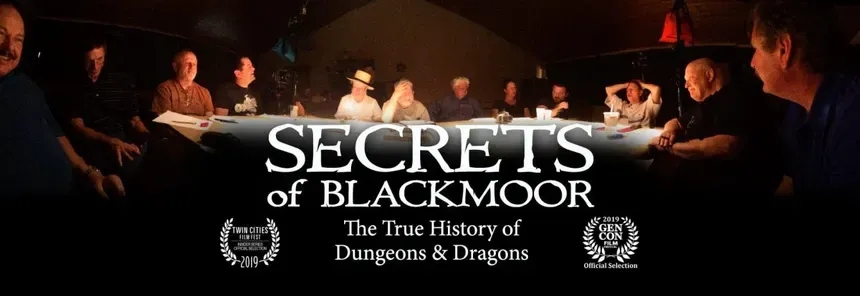

For those ready to dive deeper and tap into the heart of that early spirit, I highly recommend the documentary Secrets of Blackmoor. It’s an eye-opener.

Further Exploration

- Subreddits: r/odnd, r/osr, r/fkr

- Website: secretsofblackmoor.com (for more on the documentary)

Member discussion: